Beginning in 2017, I immersed myself in the earliest history of the first professional journalistic fact-checkers, a role created by TIME in 1923 and held exclusively by women until 1971. In every published account of TIME’s founding, the fact-checkers went unnamed, if mentioned at all.

Combing through hundreds of letters, memos, and records in the TIME corporate archive I found few first-person accounts of the women’s experiences remain. Instead, their stories are told through the preserved internal correspondences of their male colleagues: hand-drawn cartoons, scribbled notes, reminiscences, and even songs—a sustained male gaze through which the fact-checkers and their work was seen, recorded, and mythologized.

Against the Best Possible Sources (an installation organized by Olivia Smith, director of Magenta Plains, New York) conflates the loss of primary sources with the untold stories and contributions of the early fact-checkers. Decommissioned bookshelves from the Fondren Library are presented as skeletal remains emptied of their contents.

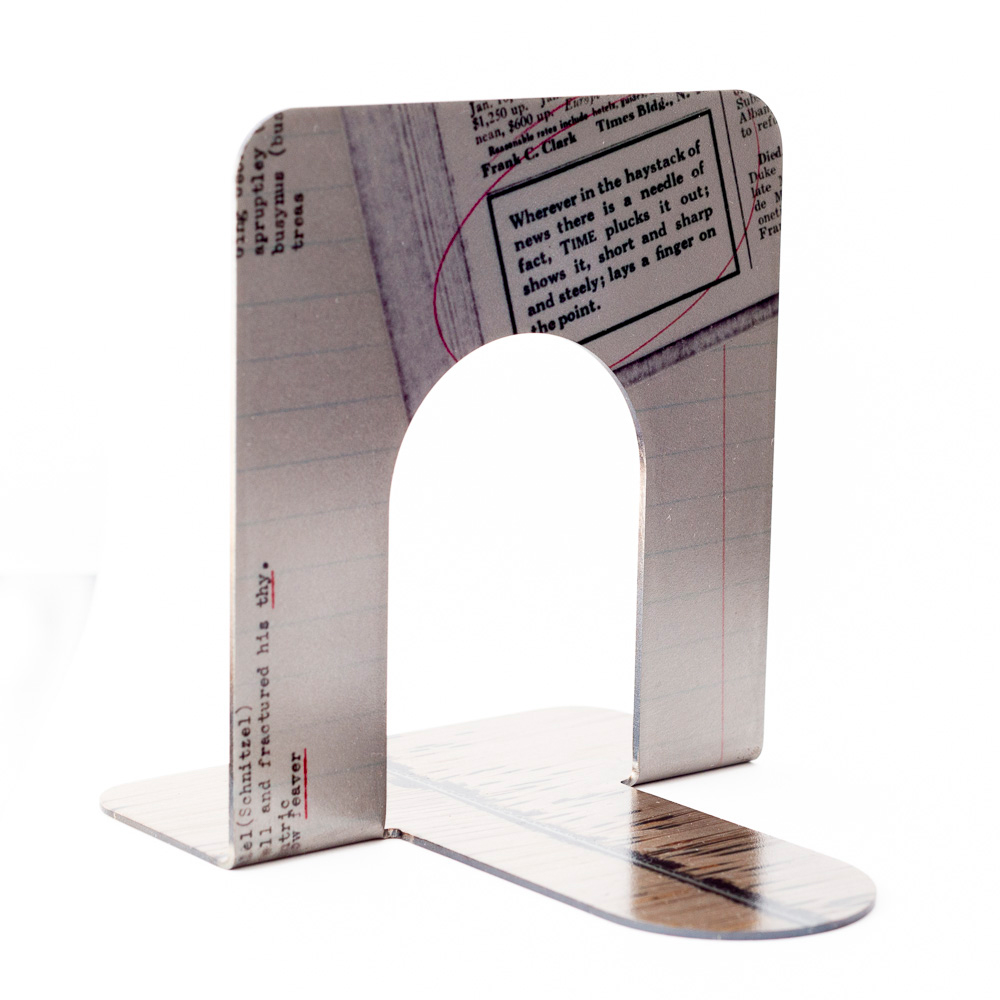

Scattered throughout the emptied shelves are 12 unique, artist-made steel bookends rendered useless. The bookends’s surfaces appear imprinted by lost documents: images of found artifacts entombed in TIME’s archive. The bending of the steel plates allow for documents from different eras of TIME to overlap

and collide.

Only deaccessioned library books of The Bible, Homer’s Iliad, and Xenophon’s Anabasis linger, replicating TIME’s first reference library now deemed unwanted.

A Kodak Carousel slide projector flickers in the back of the gallery briefly illuminating photographs, internal memos, documents, and other ephemera which shed light on the original fact-checkers. The projected images were made with a cell phone when visiting the archive and translated into slide film, which conveys the seemingly credible formality of a slide lecture. The artist’s hand can be seen arranging and proffering the documents—the limb of a disembodied researcher comingling with the unidentified individuals in the pictures. Over the course of the installation, the images slowly degrade as they are blasted by the continuous heat of the carousel’s bulb.

In timed intervals, an audio piece fills the space with what initially seems like a reading of a first-hand account of one of the early fact-checkers. However the script was composed entirely of disparate texts sourced from TIME archive, decontextualized and reconstructed creating a new, fabricated narrative. Clippings of the sourced statements are provided to the audience as an open edition artist book, titled Sources.

The installation presents the most comprehensive account of the first fact-checkers that exists today while simultaneously highlighting the gaps in history and the dearth of reliable sources. All together, I am fact-checking the history of fact-checking—reperforming the fact-checker’s labor and embodying the processes invented by the women themselves.